For decades there have been international efforts to collaborate in addressing causes of health issues affecting people around the world. The subject of alcohol consumption has been included in such efforts as it is accepted as a cause of serious diseases; where it's less clear, and hence the subject of debate among professionals and scholars, has been around the effects (and side effects) of smaller quantities.

My impression as a non-specialist is that until recently, some international data has been published, but the samples have often been either quite small or selective. Generally, collaborations have involved a few partners, but it’s not been global. Apart from the challenge of coordination, the funding required for large scale studies is considerable and has tended to be dependent on philanthropic organisations or big businesses. Such has been the case for alcohol, at least in the UK, where one of the most highly visible charities, Drinkaware, works closely with the alcohol industry, a relationship that, as the Aberdeen Evening News reminds us, continues to be problematic.

So I think it’s of major importance that the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), at the University of Washington, has coordinated work in this field involving hundreds of researchers from accredited public institutions spanning much of the world. Their collaboration has resulted in the publication of Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease 2016 Study in The Lancet (full report). This research — and many of the other projects as well as the open access — is funded by the Bill & Melissa Gates Foundation (which makes sense as Microsoft is based in Seattle), with no obvious potential conflict of interest in this area.

The research gathers data mainly via questionnaires seeking to establish current practices in alcohol consumption. Whereas some studies had suggested health benefits with low levels of consumption, they dismiss this assertion, stating in their conclusions:

The study appears to meet expectations around rigour, but the main issue is how to interpret the findings. What’s the significance? Does it really matter for the ‘occasional drinker’? Based on their statistical analysis, the percentage improvements are small, suggesting that the benefits of complete abstention are minor. In some comments reported at the end of a BBC article about the research, No alcohol safe to drink, global study confirms, Prof. David Spiegelhalter, Winton Professor for the Public Understanding of Risk at the University of Cambridge, was dismissive.

Prof. Spiegelhalter, who introduced the MicroLives metric, is an expert at quantification and risk around health and based on the available data it’s a reasonable conclusion to reach; the measurements of the purely physical symptoms appear to be statistically trifling.

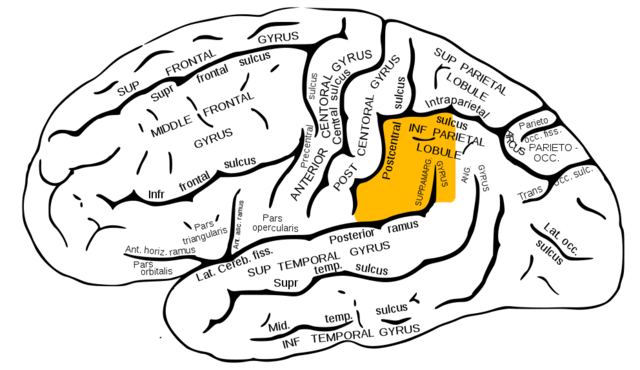

But where alcohol is concerned we ought to be looking more widely to get the full picture of its effects. With regards to these kinds of studies, one could seek longitudinal studies that studied changes in intake over a period of time, but it will probably be more revealing to concentrate on cognitive effects, which can be studied in neuroscience; in particular how an individual’s perception of their quality of awareness might not register a degradation in, e.g., response times. Is it possible to measure the impact on decision-making processes in general?

The design of the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study is based on certain kinds of measurements relating to a person’s health, but if a government, public body or policy maker wishes to evaluate alcohol effects more fully, then other perspectives are needed. So I want to extend the discussion, starting with the observation about alcohol’s pervasiveness: just as alcohol gets very rapidly absorbed by the bloodstream, there’s a social currency or flow around alcohol — I’ll dub it ‘society under the influence’. I suggest that it has an impact on even clinical research studies, for any research around human behaviour depends on views and the socio-cultural context.

To get some indication of this, I’m curious to know how the findings have been received in different countries. What do people make of it? One way of gauging this is to look at how the research has been reported in national media channels. If we choose to examine responses in the UK, which is a largely secular society, there is strong emphasis on ‘objectivity’ and empirical research based on verifiable evidence. Looking again at the BBC’s report, whilst the findings are duly summarised, the suggested ‘takeaway’ for the reader is strongly suggested by Spiegelhalter’s remarks, which I paraphrase as: “nothing to see here, carry on as normal.” It’s echoed numerous times (along with the derisory tone) in the comments section.

However, those who have the responsibility to ensure safety on the roads often advise that any amount could be a problem. Alcohol increases risks generally and as to pleasurable experiences, there are many free alternatives (such as meditation) that don’t carry such risk. Moreover alcohol’s biggest risk is not the physical effects, but the increase in heedlessness (which in turn increases exposure to risk). Furthermore, many people do recommend abstention, especially those who practice a religion (in Christianity, think about the temperance movement; in Islam the prohibition on alcohol; and in Buddhist the Fifth Precept. They regard it as poison, which immediately makes an argument for adopting such a position. But practice varies enormously due to cultural conditioning, as I established when I carried out my own survey online.

Britain has a long-standing culture of alcohol, where any number of explanations are readily forthcoming (such as alcohol is needed to keep people warm — to which one may point out that the Cadbury family’s hot chocolate business demonstrated no such need.) Some are very protective about drinking habits, which reflects the social function, but the gathering down the local pub doesn’t need to be fuelled by alcohol as there are many other beverages that could take their place. It spans all social strata, particularly noticeable at Oxford University, where so much social networking revolves around it (many academics are partial to a glass of fine wine), though it’s not so pronounced as before. It even affects Buddhist scholarship; if an academic interprets the precept around refraining from intoxicants as “not to take alcohol to the point of intoxication” then it’s quite likely that they drink alcohol! But from my own reading of canonical sources the Buddha was clear — to be safe, “not a drop” should be consumed.

The Buddha taught in a way that both enabled an individual to cultivate their mind, but also to foster the social conditions in which individuals practice. Returning to GBD study, it was the World Bank who sponsored initial work in 1990, subsequently reported in the World Development Report 1993 : Investing in Health (see the section on ‘Measuring the burden of disease’, pp. 25-29). In that report from 25 years ago there was already established a way of measuring reduced quality of life as disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Although there was no explicit mention in this section of alcohol, it is mentioned in other sections as a factor in violence against women, and as a factor in high spending in low income families correlated to medical conditions (p.44). More generally this work also indicates severe social costs not measured. And one can take this further by consider the non-physical and even metaphysical implications: in Buddhism, the link between alcohol and dementia is clear:

The greatest danger from alcohol is the risk of heedlessness, which can lead to any number of problems, for the individual and others, which may or may not have observable impact on physical health. It can lead someone to think that an extra glass is okay and then this process can keep repeating and there lies the danger — as recovering alcoholics will insist very strongly. The effects are determined by the Law of Karma and taking alcohol is described as a road to ruin. It’s really not worth the risk.

My impression as a non-specialist is that until recently, some international data has been published, but the samples have often been either quite small or selective. Generally, collaborations have involved a few partners, but it’s not been global. Apart from the challenge of coordination, the funding required for large scale studies is considerable and has tended to be dependent on philanthropic organisations or big businesses. Such has been the case for alcohol, at least in the UK, where one of the most highly visible charities, Drinkaware, works closely with the alcohol industry, a relationship that, as the Aberdeen Evening News reminds us, continues to be problematic.

So I think it’s of major importance that the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), at the University of Washington, has coordinated work in this field involving hundreds of researchers from accredited public institutions spanning much of the world. Their collaboration has resulted in the publication of Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease 2016 Study in The Lancet (full report). This research — and many of the other projects as well as the open access — is funded by the Bill & Melissa Gates Foundation (which makes sense as Microsoft is based in Seattle), with no obvious potential conflict of interest in this area.

The research gathers data mainly via questionnaires seeking to establish current practices in alcohol consumption. Whereas some studies had suggested health benefits with low levels of consumption, they dismiss this assertion, stating in their conclusions:

“Our results show that the safest level of drinking is none. This level is in conflict with most health guidelines, which espouse health benefits associated with consuming up to two drinks per day.”

The study appears to meet expectations around rigour, but the main issue is how to interpret the findings. What’s the significance? Does it really matter for the ‘occasional drinker’? Based on their statistical analysis, the percentage improvements are small, suggesting that the benefits of complete abstention are minor. In some comments reported at the end of a BBC article about the research, No alcohol safe to drink, global study confirms, Prof. David Spiegelhalter, Winton Professor for the Public Understanding of Risk at the University of Cambridge, was dismissive.

"Given the pleasure presumably associated with moderate drinking, claiming there is no 'safe' level does not seem an argument for abstention," he said.

"There is no safe level of driving, but the government does not recommend that people avoid driving.

"Come to think of it, there is no safe level of living, but nobody would recommend abstention."

Prof. Spiegelhalter, who introduced the MicroLives metric, is an expert at quantification and risk around health and based on the available data it’s a reasonable conclusion to reach; the measurements of the purely physical symptoms appear to be statistically trifling.

But where alcohol is concerned we ought to be looking more widely to get the full picture of its effects. With regards to these kinds of studies, one could seek longitudinal studies that studied changes in intake over a period of time, but it will probably be more revealing to concentrate on cognitive effects, which can be studied in neuroscience; in particular how an individual’s perception of their quality of awareness might not register a degradation in, e.g., response times. Is it possible to measure the impact on decision-making processes in general?

The design of the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study is based on certain kinds of measurements relating to a person’s health, but if a government, public body or policy maker wishes to evaluate alcohol effects more fully, then other perspectives are needed. So I want to extend the discussion, starting with the observation about alcohol’s pervasiveness: just as alcohol gets very rapidly absorbed by the bloodstream, there’s a social currency or flow around alcohol — I’ll dub it ‘society under the influence’. I suggest that it has an impact on even clinical research studies, for any research around human behaviour depends on views and the socio-cultural context.

To get some indication of this, I’m curious to know how the findings have been received in different countries. What do people make of it? One way of gauging this is to look at how the research has been reported in national media channels. If we choose to examine responses in the UK, which is a largely secular society, there is strong emphasis on ‘objectivity’ and empirical research based on verifiable evidence. Looking again at the BBC’s report, whilst the findings are duly summarised, the suggested ‘takeaway’ for the reader is strongly suggested by Spiegelhalter’s remarks, which I paraphrase as: “nothing to see here, carry on as normal.” It’s echoed numerous times (along with the derisory tone) in the comments section.

However, those who have the responsibility to ensure safety on the roads often advise that any amount could be a problem. Alcohol increases risks generally and as to pleasurable experiences, there are many free alternatives (such as meditation) that don’t carry such risk. Moreover alcohol’s biggest risk is not the physical effects, but the increase in heedlessness (which in turn increases exposure to risk). Furthermore, many people do recommend abstention, especially those who practice a religion (in Christianity, think about the temperance movement; in Islam the prohibition on alcohol; and in Buddhist the Fifth Precept. They regard it as poison, which immediately makes an argument for adopting such a position. But practice varies enormously due to cultural conditioning, as I established when I carried out my own survey online.

Britain has a long-standing culture of alcohol, where any number of explanations are readily forthcoming (such as alcohol is needed to keep people warm — to which one may point out that the Cadbury family’s hot chocolate business demonstrated no such need.) Some are very protective about drinking habits, which reflects the social function, but the gathering down the local pub doesn’t need to be fuelled by alcohol as there are many other beverages that could take their place. It spans all social strata, particularly noticeable at Oxford University, where so much social networking revolves around it (many academics are partial to a glass of fine wine), though it’s not so pronounced as before. It even affects Buddhist scholarship; if an academic interprets the precept around refraining from intoxicants as “not to take alcohol to the point of intoxication” then it’s quite likely that they drink alcohol! But from my own reading of canonical sources the Buddha was clear — to be safe, “not a drop” should be consumed.

The Buddha taught in a way that both enabled an individual to cultivate their mind, but also to foster the social conditions in which individuals practice. Returning to GBD study, it was the World Bank who sponsored initial work in 1990, subsequently reported in the World Development Report 1993 : Investing in Health (see the section on ‘Measuring the burden of disease’, pp. 25-29). In that report from 25 years ago there was already established a way of measuring reduced quality of life as disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Although there was no explicit mention in this section of alcohol, it is mentioned in other sections as a factor in violence against women, and as a factor in high spending in low income families correlated to medical conditions (p.44). More generally this work also indicates severe social costs not measured. And one can take this further by consider the non-physical and even metaphysical implications: in Buddhism, the link between alcohol and dementia is clear:

For one reborn as a human being drinking liquor and wine at minimum conduces to madness.

Anguttara Nikaya 8:40, trans. Bhikkhu Bodhi,

The greatest danger from alcohol is the risk of heedlessness, which can lead to any number of problems, for the individual and others, which may or may not have observable impact on physical health. It can lead someone to think that an extra glass is okay and then this process can keep repeating and there lies the danger — as recovering alcoholics will insist very strongly. The effects are determined by the Law of Karma and taking alcohol is described as a road to ruin. It’s really not worth the risk.