[Updates

16/1/2022: In the title, I replaced 'disciplinary' with 'methodological' as there might be a misreading of the former's meaning;

17/1/2022: confirmed Frisinghelli and Schulteis as curators]

There have for several years been frequent media reports about the various harms caused by large social media enterprises, particularly Facebook. In spite of the alarm having been raised, occasionally by senior figures such as Sean Parker who warned of its effects on the brain, the businesses have kept on rolling and continue to do so in the face of horrifying testimony divulged by content moderators. In response, Facebook typically claims that the millions they have invested in research into the impact of well-being demonstrates a generally positive impact. Even if they were to pour billions more into their research, they would arguably reach the same conclusion. Why? Not because of a deliberate policy to evade, but because their research into well-being is based on ‘social capital’, a vaguely defined concept with flaky interpretations.

I had started drafting a section on this for my Jubilee Centre paper on virtues in the digital world. I wanted to highlight the considerable influence of this term, though the paper is mainly concerned with cognitive interventions to protect one’s awareness. I eventually omitted discussion of social capital because the paper was getting lengthy; I felt the need to include quite a bit of preparatory material to an audience unfamiliar with the Buddhist approach I was adopting.

Investigating the Origins of a Notion

So I introduce my thinking on social capital here, initially recapitulating the concern around academic notions, which I first expressed in a paper on sustainable social networking architectures I gave in 2010 (see bottom of first page), and then, in revised form, in Buddhism and Computing (chapter 5), which I largely quote here.

When delving into this, the first problem I came across was the lack of a standard definition, though a certain underlying pattern may be discerned in how systems have been built so far and it carries great significance. I am particularly grateful to Professor Alejandro Portes, former President of the American Sociological Association, for providing a very useful (and intelligible to me, a non-sociologist) historical overview in Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology. Portes observed that its sense has broadened from pertaining fundamentally to the individual and their family kinships – rooted in the foundational work of nineteenth century sociologists, particularly Émile Durkheim – to larger-scale social integration. He credits its first systematic treatment to Pierre Bourdieu, who defined it (for an individual) as

the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalised relationships of mutual acquaintance or recognition – or in other words, to membership in a group…

(The Forms of Capital, page 21, or page 247 in Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (Richardson JG, editor).)

Portes illustrates how the research, whilst aspiring to social cohesion, has in fact given rise to many theories that appear equally to allow both positive and negative networks. The latter include “exclusion of outsiders, excess claims on group members, restrictions on individual freedoms, and downward leveling norms” (page 15). With definitions being vague or ambiguous, he observes that the personal concept of ‘social capital’ based on kinship relationships has gradually evolved to become more impersonal and more generalised.

Indeed, Bourdieu’s definition could be satisfied by many kinds of entities, including federated Internet-based software services, i.e., the systems in which the social capital is being established online. Whilst these services are like the close-fitting manifestations or shadows of human activity, they should not be equated with human relationships themselves – if you get to know someone by email, it is evidenced by a record of correspondence; but if you then meet in person, you do not need that record or email itself to continue developing the friendship.

The system logs are heavily identified with human activity, and with the interpersonal relationships themselves. Whilst this readily enables quantification and basic usage figures as garnered for analytics, much of the analysis needs careful interpretation and further in-depth enquiry, for which self-responses to a shopping list of questions are surely inadequate. It is thus unsurprising that the findings with regard to well-being are very mixed, even in the interpretation of identical data, giving the tech companies a great deal of wiggle room to convince (delude?) themselves that their systems really are conducive to well-being.

Le capital social est l’ensemble des ressources actuelles ou potentielles qui sont liées à la possession d’un réseau durable de relations plus ou moins institutionnalisées d’interconnaissance et d’inter-reconnaissance, ou, en d’autres termes, à l’appartenance à un groupe …

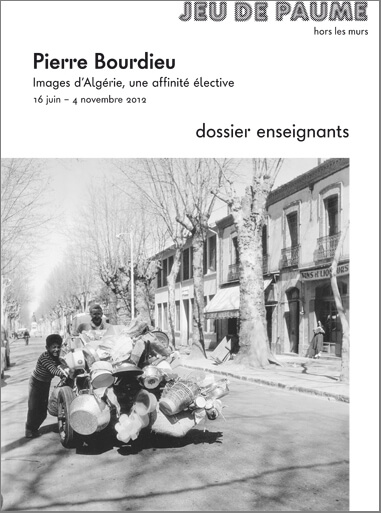

Images d’Algérie: An Exhibition of Ethnographic Photography

“The exhibition "Pierre Bourdieu. Images of Algeria" shows the photographic works of Pierre Bourdieu, taken during his fieldwork between 1958 and 1961, in the period of the war of liberation in Algeria. The exhibition places these photographic documents in the context of Bourdieu's ethnographic and sociological studies of that time. Bourdieu's pioneering field research, which is here supplemented by his own photographs, provides an insight into the development of his sociological tenets. In addition to illuminating the evolution of his work, the photographs are also impressive documents of social history, which — even after five decades — have lost none of their immediacy and relevance.”

Power as Capacity

… grâce à ce capital collectivement possédé, un pouvoir sans rapport avec son apport personnel, chaque agent participe du capital collectif, symbolisé par le nom de la famille ou de la lignée, mais en proportion directe de son apport, c’est-à-dire dans la mesure où ses actions, ses paroles, sa personne font honneur au groupe

… then thanks to this collectively owned capital, a power unrelated to their personal contribution, each agent participates in the collective capital, symbolized by the name of the family or lineage, but in direct proportion to his contribution, that is to say to the extent that his actions, words, and person honour the group

pouvoir (faculté) (gén) power; (capacité) ability, capacity; (Phys, gén: propriété). avoir le ~ de faire to have the power ou ability to do; il a le ~ de se faire des amis partout he has the ability to make friends everywhere; il a un extraordinaire ~ d’éloquence/de conviction he has remarkable ou exceptional powers of oratory/persuasion; ce n’est pas en mon ~ it is not within ou in my power; it is beyond my power; il n’est pas en son ~ de vous aider it is beyond ou it does not lie within his powers to help you; il fera tout ce qui est en son ~ he will do everything (that is) in his power ou all that can possibly be done; ~ couvrant/éclairant covering/lighting power; ~ absorbant absorption power, absorption factor.

(= influence, autorité) power

Le Premier ministre a beaucoup de pouvoir. The prime minister has a lot of power.

avoir pouvoir de faire (= autorisation) to have the authority to do ⧫ to have authority to do; (= droit) to have the right to do

Lost in Translation?

I would like, within the limits of a lecture, to try and present the theoretical principles which are at the base of the research whose results are presented in my book Distinction (Bourdieu 1984a), and draw out those of its theoretical implications that are most likely to elude its readers, particularly here in the United States, due to the differences between our respective cultural and scholarly traditions

I think that it is particularly necessary to set the record straight here: indeed, the hazards of translation are such that, for instance, my book Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture (Bourdieu and Passeron 1977) is well known, which will lead certain commentators…

In the more general sense it has in the 'symbolic economy' which has been Bourdieu's chief concern, capital consists in the power to control and use the means and social mechanisms required for cultural production to shape perception and understanding in accordance with the shapers' views and interests. The differential distribution of all forms of capital among agents and groups of agents determines their position in the social space of dominant and dominated classes. Their position in turn determines their habitus – the 'system of durable, transposable dispositions, structured structures predisposed to function as structuring structures [which constitutes] the socially informed body, with its tastes and distastes, its compulsions and repulsions … '

Here too the notion of cultural capital did not spring from pure theoretical work, still less from an analogical extension of economic concepts. It arose from the need to identify the principle of social effects which, although they can be seen clearly at the level of singular agents—where statistical inquiry inevitably operates—cannot be reduced to the set of properties individually possessed by a given agent.

I would reinforce what Bourdieu is intimating and assert that the notions he puts forward can barely be understood without attending to the practical context over an extended period; the visuals informed his analysis deeply after due reflection. It confirms for me that it is unrealistic to think that one can gain more than a shallow insight into social capital generated by people’s online activities through usage analytics and surveys alone.

Glimpses of a Buddhist Response

the socially informed body, with its tastes and distastes, its compulsions and repulsions, with, in a word, all its senses not only the traditional five senses, but also the sense of necessity and the sense of duty, the sense of direction and the sense of reality, the sense of balance and the sense of beauty, common sense and the sense of the sacred, tactical sense and the sense of responsibility, business sense and the sense of propriety, the sense of humour and the sense of absurdity, moral sense and the sense of practicality, and so on'.

“What is good, what is bad? What is right, what wrong? What ought I to do or not to do? What, when I have done it, will be for a long time my sorrow ... or my happiness?”

To address these concerns we can extend the orthogonality above into another dimension (the 7th as it happens!) and reserve this for [especially commercial] organisations. There can be different groups reflecting the types of organisations, ranging from makers of the social networking site, through your alma maters and charities you support to others you've never even heard of. In a similar manner to relationships with individuals, you can define what access these classes of organisations can have to your data - it should all be clearly accessible, albeit with suitable abstraction, where you can drill down to identify the details of any organisation that has access to your data and clearly see at a glance what they can use. All system features (such as applications that you plug in) should be dependent upon these settings. If you are offered an app from an unknown organisation, then various details about the organisation should be readily available and what the use of the app [not just by you, but by anyone] will mean in terms of access to your data.