The ‘attention economy’ has become a way large organisations view our use of the Internet; to maximise revenues, systems are designed to retain and nurture our attention, to keep us in front of screens and to steer us in particular directions, usually feeding some form of consumerism.

Perhaps because of the novelty in social media, Web 2.0, etc. and the undoubted benefits of connecting people irrespective of their location, mainstream publicity has for many years been generally positive and upbeat, and it is only belatedly that concerns expressed about the impact on one’s mental state and well-being (and hence for society as a whole) have started to be taken seriously. However, these concerns are growing, especially evident among those behind such technological developments, who, as parents, are instructing nannies to prevent their children from having access to such devices.

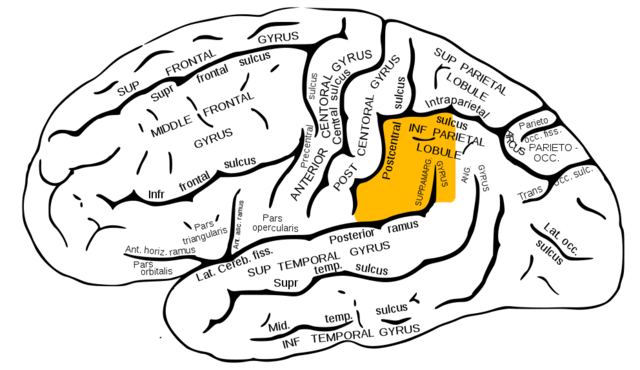

Figure: The supramarginal gyrus (shaded in yellow), which has been found to be associated with empathy.

In this introductory post (the first of probably two or three) I’ll try and articulate some of the underlying issues and indicate how I am developing a cognitive approach, extending previous work from a social sciences perspective. My interest in cognitive aspects of behaviour in online environments was sparked whilst leading the RAMBLE project in mobile blogging, 2004-5. Ostensibly a software development project, I noticed that the content being authored had a special reflective quality, as remarked in an article for Ariadne.

Although I don’t have empirical data to show this, I’m quite sure that cognitively what was essential to the depth and range of student reflection was dis-engagement, allowing the mind to relax and unbind and to come to a natural position of rest before reasoning and evaluating with greater clarity. (Note I used “unbind” deliberately, because the meaning of engagement has a sense of binding.)

So an intervention is an act of coming between someone on an existing course or path and the continuation of that path. That ‘act’ could be a natural phenomenon, as in “bad weather intervened in the rescue operation”, but, more usually, when it involves people, there is some intention behind the intervention with a view to modifying the outcome.

Here are a few examples:

Does that matter? What is the human impact? In the short term (for example, in the immediate mental functioning) and in the long term (for example, in emotional development)? Evidently, the prompts above are designed to hold on to and retain attention, i.e. keep the user engaged, just for a few more moments. A handful of such prompts are easily dealt with, but what about the cumulative effect of dozens, hundreds, or thousands … ?

Recently there have been candid remarks from a number of prominent figures that indicate that the cognitive and emotional effects are deleterious. Most notably, perhaps, was the reference to a so-called ‘dopamine hit’, by Sean Parker, former President of Facebook, when interviewed for Axios. The design of social networking sites (SNS) and social media technology is by and large making attention an increasingly scarce resource and it thereby is often removing control; malware often spreads when a usually vigilant person is in a hurry to clear their desk and in their haste they click on the wrong link. We tend to think of succumbing to malware in terms of software viruses causing damage to our daily working routines or finances, but Parker has made it clear that badly designed SNS can exploit “human vulnerability” in a similar way by facilitating harmful speech in status updates and accepting ‘friend’ connections without any thought.

I think we need also to be constructive, by proposing alternative technological designs: as Rohan Gunatillake, creator of the Buddhify app, has argued, this requires that practitioners and academics embrace the digital. Design shouldn’t be left to a small demographic of young technically-savvy coders. Rohan advocates ‘compassionate’ elements to gradually improve the quality of existing designs, which can include softening current interventions (such as replacing an unhelpful alert ‘You’ve got 10,000 messages in your InBox’ with colour saturations for new messages). However, whilst such measures offer some help I see them as minor concessions, which will be insufficient to deal with fundamental flaws (to borrow a biblical image, this is like “pouring new wine into old wineskins”).

Seeing the need to start afresh, I have for some time been focusing on the theme of well-being rooted in teachings of the Buddha, whilst drawing on a wide range of scholarly disciplines. Previously I explored the architecture of relationship networks from social science perspectives, resulting in ‘Supporting Kalyāṇamittatā Online: New Architectures for Sustainable Social Networking’ (paper and slides on the siga.la project). The conference where that paper was given had three strands: Buddhism and Social Science, Buddhism and Cognitive Science, and Buddhism and Natural Science.

The social science perspective has been helpful in providing some background and general parameters for the design. Indeed, much of the foundational work has already been established concerning notions of friendship, well-being and human welfare, though research tends to drift in particular directions, neglecting others. In social sciences, a central term is ‘social capital’, which rather vaguely attributes value to the various ways of being sociable — a Wikipedia article seems to cover this quite well. Alejandro Portes attempted to provide a firmer footing (in Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology) and made an important observation that there’s been a gradual shift in how it’s viewed, moving away from small-scale family (kinship) relationships, the original focus for Durkheim, to large-scale societal views. Since that paper, now 20 years old, many SNS studies have reflected that tendency by dwelling on the collective paradigm.

This has arguably resulted in ethics being a casualty because discussion in this area has been more in terms of personal data and privacy and far less about behaviour. It partly explains how Janet Sternberg’s thesis from 2001 (almost a prehistoric age in Web terms) about misbehaviour in cyber places can be republished in 2012 for, as she explains, there still remains a dearth in literature about behaviour (as well as showing that the principles of community remain largely the same). By introducing normative Buddhist ethics (above) I have tried to highlight how this is the case, but haven't yet got so far in applying this practically to software development. I have been exploring more at a theoretical level the synergies with social science and whilst findings from social sciences, particularly around patterns of human networking, have influenced designs (with research often commissioned by larger tech companies), they are generally not affecting the basic structure.

For more fundamental aspects concerning the system architecture and user interfaces, further and perhaps deeper insights may be gained by appeal to cognitive science. Social sciences is effective in showing how just as the physical environment impacts our ability to grow socially, so too the online environment, in terms of types of networks and relationships; cognitive science is more focused on the individual person and, like a microscope, potentially able to illuminate the basic qualities and degree of cognitive processing involved at every step. An interdisciplinary approach will be more fruitful, as shown by the work in evolutionary anthropology by Robin Dunbar around the "social brain hypothesis", popularly headlined by Dunbar's Number. This has even spawned social networking services such as the Path app, as featured on Wired, with network size limited by that number.

In other words, there is at the basic level of cerebral functioning, a certain minimum duration required to absorb and process. I suspect that minimum is for survival and if this exposure were sustained for a long time, then perhaps more neural connections would be established, a kind of adaptation that ensured continuation in terms of essential biological functioning. In the context of behaviour online, it means that the brain can develop ways to cope with the barrage of interventions, but what about the overall health and what would that mean in terms of more refined human qualities?

The team subsequently emphasized that time was of the essence. Interviewed for USC News, Noble Instincts Take Time, Immordino-Yang remarked:

I take that as a cue for designing interventions in a new, wholesome way. But it will takes more than one "magic number" to foster a radically new approach to system and interaction that could provide an alternative to the most popular systems in use.

So let’s see if we can show how the use of new kinds of interventions as an aspect of design in SNS can enhance the quality of attention and decision-making. Can we in particular deploy interventions to enable users to take more time for reflection and evaluation online? Can we do this especially with a view to the cultivation of virtue, which will aid in our personal development and the fostering of healthy relationships?

Our efforts should pay more attention to individual behaviour, especially on how to make choices more skilfully; this is where interventions can be introduced. Friendship is a pertinent focus because it applies to many scenarios where one’s actions have some impact on the quality of one’s relationship with others. Actually, many kinds of interventions can be specified to enhance friendship with various spheres of impact, amply demonstrated in a valuable reference paper by Adams and Blieszner, Resources for Friendship Intervention. Their investigations reveal their intricate nature and considerable variety; they are sensitive to how effects can be unpredictable. They also discuss how cognitive processes can be uplifting (page 162):

There is a section devoted to 1-1 (dyadic) relationships, which is discussed in terms of marital partnerships, but even in that context it is recognised that:

Think about the online context — how much autonomy do we really have and what is our emotional state in our interactions?

It needs pause for thought, and in the next post I'll show how interventions can help.

Perhaps because of the novelty in social media, Web 2.0, etc. and the undoubted benefits of connecting people irrespective of their location, mainstream publicity has for many years been generally positive and upbeat, and it is only belatedly that concerns expressed about the impact on one’s mental state and well-being (and hence for society as a whole) have started to be taken seriously. However, these concerns are growing, especially evident among those behind such technological developments, who, as parents, are instructing nannies to prevent their children from having access to such devices.

Figure: The supramarginal gyrus (shaded in yellow), which has been found to be associated with empathy.

In this introductory post (the first of probably two or three) I’ll try and articulate some of the underlying issues and indicate how I am developing a cognitive approach, extending previous work from a social sciences perspective. My interest in cognitive aspects of behaviour in online environments was sparked whilst leading the RAMBLE project in mobile blogging, 2004-5. Ostensibly a software development project, I noticed that the content being authored had a special reflective quality, as remarked in an article for Ariadne.

Although I don’t have empirical data to show this, I’m quite sure that cognitively what was essential to the depth and range of student reflection was dis-engagement, allowing the mind to relax and unbind and to come to a natural position of rest before reasoning and evaluating with greater clarity. (Note I used “unbind” deliberately, because the meaning of engagement has a sense of binding.)

Definition

I am going to take the principles of engagement and disengagement to explore a particular facet in design: the intervention. This word is derived from two Latin words: inter, which means ‘between’ and venire, a verb meaning ‘to come’. (See the entry on the online etymology dictionary.)So an intervention is an act of coming between someone on an existing course or path and the continuation of that path. That ‘act’ could be a natural phenomenon, as in “bad weather intervened in the rescue operation”, but, more usually, when it involves people, there is some intention behind the intervention with a view to modifying the outcome.

The Problem: Interventions and Attention Deprivation

At first I thought that the concept of intervention was confined largely to medical sciences, e.g. to help someone who suffers from dyslexia improve the accuracy of their reading. However, as I explored I realized that its use is not restricted to any particular subject or field of application: regarding software and the Internet, there are numerous kinds of interventions or, rather, micro-interventions, in the design of social networking sites, but they are not usually so helpful when repeated!Here are a few examples:

- a web page pop-up prompting us to check the site cookies policy or sign up to a newsletter

- regular and frequent e-mails conveying selected network updates. Typically they convey only summary information and require clicks to their site to see anything really useful. Some of these will link to pages requiring a paid subscription.

- Similarly, 1-1 messages may come via e-mail from a contact, but replying to the e-mail requires logging into the network.

Does that matter? What is the human impact? In the short term (for example, in the immediate mental functioning) and in the long term (for example, in emotional development)? Evidently, the prompts above are designed to hold on to and retain attention, i.e. keep the user engaged, just for a few more moments. A handful of such prompts are easily dealt with, but what about the cumulative effect of dozens, hundreds, or thousands … ?

Recently there have been candid remarks from a number of prominent figures that indicate that the cognitive and emotional effects are deleterious. Most notably, perhaps, was the reference to a so-called ‘dopamine hit’, by Sean Parker, former President of Facebook, when interviewed for Axios. The design of social networking sites (SNS) and social media technology is by and large making attention an increasingly scarce resource and it thereby is often removing control; malware often spreads when a usually vigilant person is in a hurry to clear their desk and in their haste they click on the wrong link. We tend to think of succumbing to malware in terms of software viruses causing damage to our daily working routines or finances, but Parker has made it clear that badly designed SNS can exploit “human vulnerability” in a similar way by facilitating harmful speech in status updates and accepting ‘friend’ connections without any thought.

Response: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Well-being

So how do we respond? Vociferous campaigns, such as the petition to Facebook from the Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood to withdraw Messenger Kids, advocate banning certain new software service developments. However, once released somewhere in the world, technology generally can’t be uninvented, so unless it's clearly illegal then without major societal change it’s little more than a stalling tactic. Other responses are needed. Teaching mindfulness and skilfulness in attending to (and abstinence from) Internet use, as advocated by Ravi Chandra M.D., is a valuable tool that increases our capability and capacity to deal skilfully in such scenarios. It is certainly to be encouraged, but again, just as it’s recognised that certain physical environments are not conducive to well-being and merely leaving them as-is is not desirable, the same applies online.I think we need also to be constructive, by proposing alternative technological designs: as Rohan Gunatillake, creator of the Buddhify app, has argued, this requires that practitioners and academics embrace the digital. Design shouldn’t be left to a small demographic of young technically-savvy coders. Rohan advocates ‘compassionate’ elements to gradually improve the quality of existing designs, which can include softening current interventions (such as replacing an unhelpful alert ‘You’ve got 10,000 messages in your InBox’ with colour saturations for new messages). However, whilst such measures offer some help I see them as minor concessions, which will be insufficient to deal with fundamental flaws (to borrow a biblical image, this is like “pouring new wine into old wineskins”).

Seeing the need to start afresh, I have for some time been focusing on the theme of well-being rooted in teachings of the Buddha, whilst drawing on a wide range of scholarly disciplines. Previously I explored the architecture of relationship networks from social science perspectives, resulting in ‘Supporting Kalyāṇamittatā Online: New Architectures for Sustainable Social Networking’ (paper and slides on the siga.la project). The conference where that paper was given had three strands: Buddhism and Social Science, Buddhism and Cognitive Science, and Buddhism and Natural Science.

The social science perspective has been helpful in providing some background and general parameters for the design. Indeed, much of the foundational work has already been established concerning notions of friendship, well-being and human welfare, though research tends to drift in particular directions, neglecting others. In social sciences, a central term is ‘social capital’, which rather vaguely attributes value to the various ways of being sociable — a Wikipedia article seems to cover this quite well. Alejandro Portes attempted to provide a firmer footing (in Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology) and made an important observation that there’s been a gradual shift in how it’s viewed, moving away from small-scale family (kinship) relationships, the original focus for Durkheim, to large-scale societal views. Since that paper, now 20 years old, many SNS studies have reflected that tendency by dwelling on the collective paradigm.

This has arguably resulted in ethics being a casualty because discussion in this area has been more in terms of personal data and privacy and far less about behaviour. It partly explains how Janet Sternberg’s thesis from 2001 (almost a prehistoric age in Web terms) about misbehaviour in cyber places can be republished in 2012 for, as she explains, there still remains a dearth in literature about behaviour (as well as showing that the principles of community remain largely the same). By introducing normative Buddhist ethics (above) I have tried to highlight how this is the case, but haven't yet got so far in applying this practically to software development. I have been exploring more at a theoretical level the synergies with social science and whilst findings from social sciences, particularly around patterns of human networking, have influenced designs (with research often commissioned by larger tech companies), they are generally not affecting the basic structure.

For more fundamental aspects concerning the system architecture and user interfaces, further and perhaps deeper insights may be gained by appeal to cognitive science. Social sciences is effective in showing how just as the physical environment impacts our ability to grow socially, so too the online environment, in terms of types of networks and relationships; cognitive science is more focused on the individual person and, like a microscope, potentially able to illuminate the basic qualities and degree of cognitive processing involved at every step. An interdisciplinary approach will be more fruitful, as shown by the work in evolutionary anthropology by Robin Dunbar around the "social brain hypothesis", popularly headlined by Dunbar's Number. This has even spawned social networking services such as the Path app, as featured on Wired, with network size limited by that number.

The Solution? Restoring Attention through Intervention

Long before Parker's confession, concerns had been raised among various researchers, especially by practitioners in children’s education focused on individual development over the long term. Some of the earliest empirical studies that addressed specifically emotional development among adolescents were carried out by Mary Helen Immordino-Yang et al at the University of Southern California, in interdisciplinary work that brought together experts in education and neuroscience. In an important paper, Neural Correlates of Admiration and Compassion, they described experiments to foster qualities of virtue such as compassion and observed:“In order for emotions about the psychological situations of others to be induced and experienced, additional time may be needed for the introspective processing of culturally shaped social knowledge. The rapidity and parallel processing of attention requiring information, which hallmark the digital age, might reduce the frequency of full experience.”

In other words, there is at the basic level of cerebral functioning, a certain minimum duration required to absorb and process. I suspect that minimum is for survival and if this exposure were sustained for a long time, then perhaps more neural connections would be established, a kind of adaptation that ensured continuation in terms of essential biological functioning. In the context of behaviour online, it means that the brain can develop ways to cope with the barrage of interventions, but what about the overall health and what would that mean in terms of more refined human qualities?

The team subsequently emphasized that time was of the essence. Interviewed for USC News, Noble Instincts Take Time, Immordino-Yang remarked:

“For some kinds of thought, especially moral decision-making about other people’s social and psychological situations, we need to allow for adequate time and reflection...”

I take that as a cue for designing interventions in a new, wholesome way. But it will takes more than one "magic number" to foster a radically new approach to system and interaction that could provide an alternative to the most popular systems in use.

So let’s see if we can show how the use of new kinds of interventions as an aspect of design in SNS can enhance the quality of attention and decision-making. Can we in particular deploy interventions to enable users to take more time for reflection and evaluation online? Can we do this especially with a view to the cultivation of virtue, which will aid in our personal development and the fostering of healthy relationships?

Our efforts should pay more attention to individual behaviour, especially on how to make choices more skilfully; this is where interventions can be introduced. Friendship is a pertinent focus because it applies to many scenarios where one’s actions have some impact on the quality of one’s relationship with others. Actually, many kinds of interventions can be specified to enhance friendship with various spheres of impact, amply demonstrated in a valuable reference paper by Adams and Blieszner, Resources for Friendship Intervention. Their investigations reveal their intricate nature and considerable variety; they are sensitive to how effects can be unpredictable. They also discuss how cognitive processes can be uplifting (page 162):

“Intervention thus centers on identifying irrational beliefs and sources of inappropriate schemas; analyzing the emotional and behavioral outcomes of holding those beliefs and schemas; and replacing them with more realistic, accurate, and positive ways of thinking about the self, others, and relationships.”

There is a section devoted to 1-1 (dyadic) relationships, which is discussed in terms of marital partnerships, but even in that context it is recognised that:

“it is equally important that partners maintain a degree of autonomy or self-determination … rather than responding to each other only on the basis of anxiety or other emotions.”

Think about the online context — how much autonomy do we really have and what is our emotional state in our interactions?

It needs pause for thought, and in the next post I'll show how interventions can help.